Perspective Panorama Skybox

05 Oct, 2022Midway upon the journey of our life, etc., etc., I have become fascinated by games of the 256-colour era. Maybe it’s nostalgia. Maybe I have fooled myself into thinking that low resolution is a sufficient constraint that an amateur like me might be able to actually finish a project. Maybe Mark Ferrari’s GDC talk was just really cool.

I’ve always been slightly more interested in learning about making games than in actually playing games. I watch a lot of talks and read a lot of articles, which then inspire ideas for mechanics or simulations it would be fun to play around with. But I am not really a programmer, so the prospect of creating an entire game engine in order to prototype something is too much.

Cobbling together a small demo in JavaScript, on the other hand, doesn’t seem so bad. So I plan to work through a bunch of these little ideas and share the process. I’ll be targeting either VGA-era PC or SNES graphics to keep things simple (even as it turns out replicating palette-based images are a bit of a pain in JS), and trying to ensure that the code could conceivably have run on such systems.

First up, I want to see how far we can push SNES backgrounds by rendering a skybox with perspective correction. What can a bit of clever math do within the constraints of the hardware?

SNES Mode 7

SNES background mode 7 is famous for rendering pseudo-3D landscapes in games like F-Zero and Super Mario Kart even though the console’s picture processing was very much based on 2D tiles. The short explanation is that instead of having multiple background layers like the other modes, the background in mode 7 is a single giant tile map which can be sampled from using a transformation matrix to effectively distort or rotate it. The SNES also had the ability to update hardware settings during horizontal blanking, meaning that the matrix could be modified so that each scanline was drawn with a different transformation.

The mapping of screen pixel $\vec{x}_s$ to background pixel $\vec{x}_b$ is a combination of a translation and an affine transformation, which can be expressed as a matrix equation.

\[\vec{x}_b = \begin{bmatrix} A & B \\ C & D \end{bmatrix} ( \vec{x}_s + \vec{x}_{d} - \vec{x}_c ) + \vec{x}_c\]where $\vec{x}_{d}$ offsets the screen relative to the background, and $\vec{x}_c$ changes the origin about which the transformation happens. Retro Game Mechanics Explained has a great video illustrating what this actually looks like for the SNES hardware.

We’re going to try to force this equation to display a perspective view of the inside of a sphere, aka the sky.

Perspective

Perspective projection requires us to imagine a viewer or camera looking at the world through a defined screen area. We’ll start by defining a coordinate system where x is to the right on our screen and y is up (which means that z turns out to be backward from our viewpoint in a right-handed system).

Point $\vec{x}$ in world coordinates can be expressed using typical spherical coordinates with azimuth (longitude) $\theta$ and altitude (latitude) $\phi$. We don’t need a specific radius because we’ll just be projecting the sky, so make it a unit vector.

\[\vec{x} = \begin{Bmatrix} \cos \phi \cos \theta \\ \cos \phi \sin \theta \\ \sin \phi \end{Bmatrix}\]If we define $\vec{x}_0$ to be the point in the sky at the centre of the screen, corresponding to angles $\theta_0$ and $\phi_0$, we can compute the basis vectors for the new system.

\[\begin{align} \hat{k}' &= -\frac{\vec{x}_0}{| \vec{x}_0 |} \\ \hat{i}' &= \frac{\hat{k}' \times \hat{k}}{| \hat{k}' \times \hat{k} |} \\ \hat{j}' &= \hat{k}' \times \hat{i}' \end{align}\]Using these vectors, we create a rotation matrix which will transform world coordinates into our view-aligned coordinate system.

\[\begin{Bmatrix} \vec{x}' \\ 1 \end{Bmatrix} = \begin{bmatrix} x_{i'} & y_{i'} & z_{i'} & 0 \\ x_{j'} & y_{j'} & z_{j'} & 0 \\ x_{k'} & y_{k'} & z_{k'} & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & 0 & 1 \end{bmatrix} \begin{Bmatrix} \vec{x} \\ 1 \end{Bmatrix} = M_r \begin{Bmatrix} \vec{x} \\ 1 \end{Bmatrix}\]The $4 \times 1$ vectors here represent homogenous coordinates. In Euclidean space, the fourth value is unity, but the values can all be multiplied by a scalar and the coordinates are considered to be equal. I have not come across a satisfactory notation for mixing homogenous coordinates with real vectors, so this formulation just tries to keep things clear.

Notice we are using the Cartesian basis vector $\hat{k}$ to provide us with an up-ish direction, meaning that our view will always be oriented so that positive z in the world space is up. A lot of software uses positive y as up, but that’s dumb.

Next, we need to define a projection plane perpendicular to our view. Again, we’ll simplify the usual computer graphics approach and define only the near plane at distance $N$ since we are not interested in comparing depth. If you drag the target point around in the figure below, you’ll see how the view-aligned coordinate system is converted to a position on the plane using simple similar triangles.

The value of $N$ defines the viewing angle based on its ratio to the screen dimensions. For a 90° field of view in the vertical axis, $\tfrac{2N}{H}$ would be 1.

Computing the intersection in both $x$ and $y$ and normalizing by the screen width $W$ and height $H$, we can find normalized screen coordinate $\vec{x}_n$ for our world coordinate.

\[\begin{align} x_n &= -\frac{2N}{W} \frac{x'}{z'} \\ y_n &= -\frac{2N}{H} \frac{y'}{z'} \end{align}\]We can express this in matrix form. Homogenous coordinates pop up again, this time including a non-unity value in the fourth position. In order to find $\vec{x}_n$, we’ll need to normalize the result of the matrix multiplication to convert back to Euclidean space.

\[\begin{Bmatrix} \lambda \vec{x}_n \\ \lambda \end{Bmatrix} = \begin{bmatrix} \frac{2N}{W} & 0 & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & \frac{2N}{H} & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & N & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & -1 & 0 \end{bmatrix} \begin{Bmatrix} \vec{x}' \\ 1 \end{Bmatrix} = M_p M_r \begin{Bmatrix} \vec{x} \\ 1 \end{Bmatrix}\]Putting all that together, we can transform world coordinates to our normalized screen space. Solving for azimuth and altitude, every point on the screen can now be mapped to the sky for a given view direction.

\[\begin{align} \tan(\theta_0-\theta) &= \frac{x_n}{\frac{H}{W}(\frac{2N}{H}\cos\phi_0 - \sin\phi_0 y_n)} \\ \tan\phi &= \frac{\cos \phi_0 y_n + \frac{2N}{H} \sin \phi_0}{\frac{2N}{H} \cos \phi_0 - \sin \phi_0y_n } \cos(\theta_0 - \theta) \end{align}\]So what does that look like? In the figure below, you can drag the view centre around the sky to see how the normalized screen changes shape. (Note that I have clamped the view angle so that we never look at the poles, where the math we have been using gets screwy.)

Near the horizon, the view box bulges a little at the top and bottom, and if you look closely, you’ll see that the grid is not evenly spaced. Near the poles, the edges of the box are highly nonlinear.

Best Fit

We can’t force the SNES to perform exactly the perspective transformation, but how close can we get? Let’s see what we can accomplish by finding the least squares regression between the true perspective projection and an approximation using the mode 7 matrix equation.

First, we need to map our sky and background spaces together using a common normalized texture space. (This is just a UV map, but let’s not add any more symbols.) One way to map a sphere to a single 2D plane is to use an equirectangular projection of the sphere, where longitudes are equally-spaced vertical lines and latitudes are equally-spaced horizontal lines, i.e. the projection used in the previous figure.

We’ll normalize the perspective projection by $2 \pi$, so azimuth now ranges from $0$ to $1$ and our altitude from $-\frac{1}{4}$ to $\frac{1}{4}$. We’ll also use $-\theta$ for the horizontal axis since the angle counter-clockwise from x increases to the left in our normalized screen space.

\[\begin{align} \frac{-\theta}{2 \pi} &= \frac{1}{2 \pi}\tan^{-1} \left( x_n / a\right) + \frac{-\theta_0}{2 \pi} \\ \frac{\phi}{2 \pi} &= \frac{1}{2 \pi} \tan^{-1} \left( (b/a) \middle/ \sqrt{ (x_n /a)^2 + 1} \right) \\ a &= \tfrac{H}{W}(\tfrac{2N}{H}\cos\phi_0-\sin\phi_0 y_n) \\ b &= \tfrac{H}{W}(\cos\phi_0 y_n +\tfrac{2N}{H}\sin\phi_0) \end{align}\]We’ll normalize the background space by map width $S$ and height $T$, and again, we’re going to flip an axis and use $-y_b$, because positive y is down in the background space. To normalize the screen space, we’ll have to divide by screen width $W$ and height $H$ and flip the y-direction.

\[\begin{align} \frac{x_b}{S} &= \frac{A}{S} \left( (x_n+1) \tfrac{W}{2} + x_d - x_c \right) + \frac{B}{S} \left( -(y_n-1) \tfrac{H}{2} + y_d - y_c \right) + \frac{1}{S} x_c \\ -\frac{y_b}{T} &= -\frac{C}{T} \left( (x_n+1) \tfrac{W}{2} + x_d - x_c \right) - \frac{D}{T} \left( -(y_n-1) \tfrac{H}{2} + y_d - y_c\right) - \frac{1}{T} y_c \end{align}\]We can then define the least squares error between the models as the square of the 2D distance between the respective points in our normalized texture space for a given point in our normalized screen space. Since the parameters can only be changed per scanline, we’ll define a total error by integrating over $x_n$ with all other parameters constant.

\[E = \int_{-1}^1 \left[ \left( \frac{-\theta}{2 \pi} - \frac{x_b}{S} \right)^2 + \left( \frac{\phi}{2 \pi} - \frac{-y_b}{T} \right)^2 \right] \mathrm{d}x_n\]Setting the partial differentials $\frac{\partial{E}}{\partial{A}}$, $\frac{\partial{E}}{\partial{B}}$, etc., to zero, we can solve for the values which create the minimum error. The Leibniz integral rule lets us cheat a bit and integrate the differential since the integration range is constant, but I’ll still spare you the full expansion.

\[\begin{align} A &= 3 \tfrac{1}{W} S K_1\\ B &= 0 \\ C &= 0 \\ D &= \frac{-\frac{1}{2} T K_2 - y_c}{-(y_n-1)\frac{H}{2}+y_d-y_c} \\ K_1 &= \frac{1}{2 \pi} \int_{-1}^1 x_n \tan^{-1} \left( x_n/a \right) \mathrm{d}x_n\\ K_2 &= \frac{1}{2 \pi} \int_{-1}^1 \tan^{-1} \left((b/a)/\sqrt{(x_n/a)^2+1} \right) \mathrm{d}x_n \end{align}\]The fact that $B$ and $C$ are zero makes sense as the projection of the screen onto the background is symmetric about a vertical axis. Constants $K_1$ and $K_2$ are ugly but closed-form solveable. So we’re left with determining values for the offsets $\vec{x}_c$ and $\vec{x}_d$. Using the same procedure just results in additional redundant equations, so we’ll have to pick something arbitrary but internally consistent.

First, we’ll impose the condition that both models map to exactly the same point at the view centre, where $\vec{x}_n = 0$. Then, we can pick this point (de-normalized) to be our $\vec{x}_c$ since it is the effective origin for the matrix transformation.

\[\begin{align} \frac{-\theta_0}{2 \pi} &= \frac{A}{S}(\tfrac{W}{2} + x_d - x_c) + \frac{1}{S} x_c \\ \frac{\phi_0}{2 \pi} &= -\frac{D}{T} (\tfrac{H}{2} + y_d - y_c) - \frac{1}{T} y_c \end{align}\] \[\begin{align} x_c &= S \frac{-\theta_0}{2 \pi} \\ y_c &= -T \frac{\phi_0}{2 \pi} \end{align}\]$A$ is constant, so $x_d$ is easy. It ends up being the left side of a non-transformed screen which has been offset to be centred at the view centre, which is fairly intuitive.

\[x_d = x_c - \tfrac{W}{2}\]However, $D$ is a function of $y_d$. If we try the same thing, we’re left with a bit of a problem.

\[D = \frac{-\frac{1}{2}TK_2 - y_c}{-y_n}\]Remember that the normalized screen coordinate $y_n$ has a range from $-1$ to $1$. At the centre of the screen, $D$ becomes singular! Computers tend not to like this. So we’ll need to take a different approach.

Instead, we’ll pick $y_d$ so that the denominator of $D$ is always nonzero. First, the $-(y_n-1)\tfrac{H}{2}$ term can take values from $0$ to $H$. Second, we’ve limited $\phi_0$ to range from $-\frac{\pi}{4}$ to $\frac{\pi}{4}$ to avoid looking at the poles, so $y_c$ ends up taking values from $\frac{1}{8}T$ to $-\frac{1}{8}T$. All we have to do is pick a value for $y_d$ so that $D$ is always nonsingular.

\[y_d > \tfrac{1}{8}T\]Ok! So what does that look like?

Not bad. The corners of the screen at the top and bottom of the viewable space will be the most distorted. The view centre also diverges from our control point because the curves in background space representing a horizontal line in screen space are forced to be straight.

Skybox Imagery

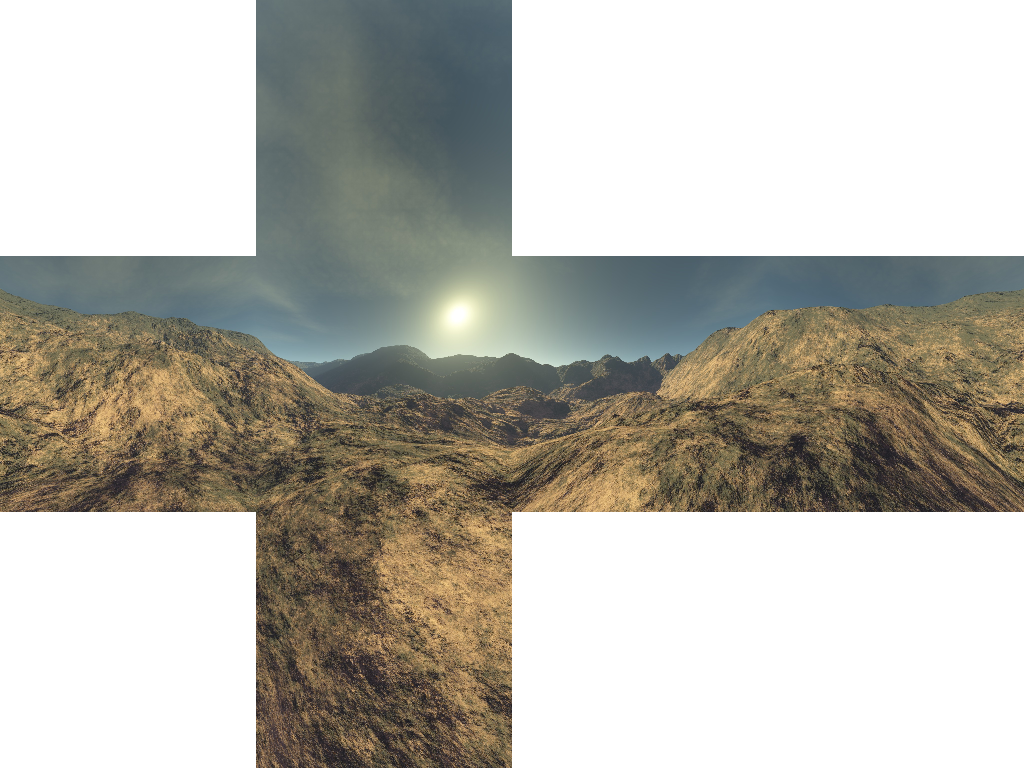

The final step is to display some imagery. I grabbed some CC-licensed art from OpenGameArt.org for demonstration purposes. Typically, a skybox is created as a cube map consisting of six images which create the inside faces of a big cube.

This needs to be converted to an equirectangular projection for our sky texture. Luckily, the six images are just perspective views using the same transformation described above. Constant $\frac{2N}{H}$ is 1 for a 90° field of view, $\frac{H}{W}$ is 1 for a square image, and the view directions are all just the positive and negative versions of the Cartesian basis vectors.

The centre of the cube map’s front face has been shifted to the left edge of the image, $x_b = 0$, and the top and bottom faces are distorted to fill its full width. The horizon, $y_b = 0$, is at the vertical centre of the image as shown; the actual background map will be two narrow strips at the top and bottom and a big empty space between. (You could conceivably use this space to draw a HUD and then switch the transform to show that on part of the screen, though mode 7 is pretty short on tiles.) I’ve also just used a quick and dirty nearest-neighbour transformation, so the image is a bit noisy.

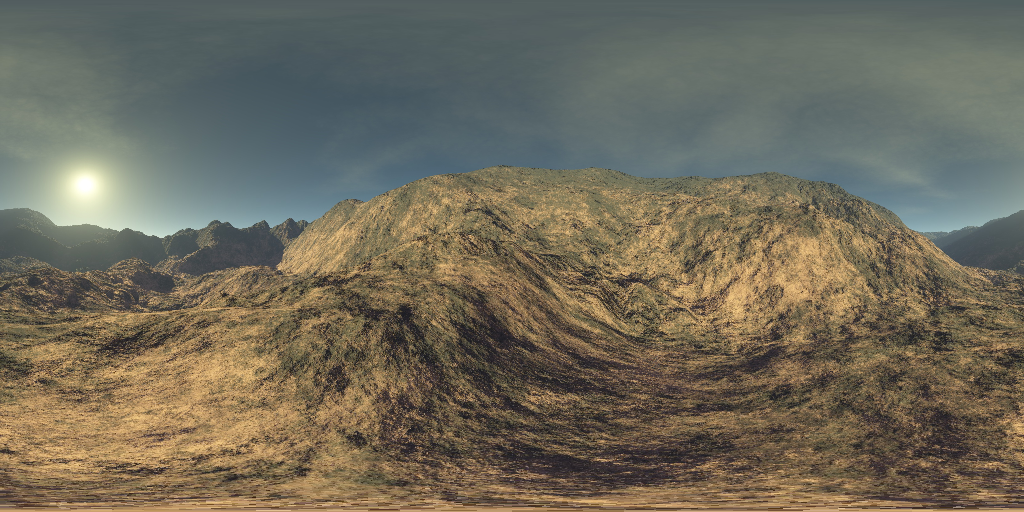

Let’s put this all together! Drag the view below to look around.

It works! Kind of. Things are ok if you keep the view near the horizon, or if you are panning up and down. It gets very strange when you look fully up or down and then rotate the view horizontally. The areas which have the largest divergence between the perspective view and the approximation are predictably the oddest-looking.

What’s Next?

This was a fun math exercise, and I’m fairly happy with the result. But what would be the next steps if I wanted to actually implement this on the SNES?

First, there is no chance these specific images can be used, so I’d have to create new art. Mode 7 only gets 256 8x8 tiles to work with, and it would take 8192 of them to draw this skybox as-is. With some clever modifications, we can likely reduce that number by finding similar tiles, but that is a big lift.

Second, the equations for constants $K_1$ and $K_2$ include inverse hyperbolic functions. Not the kind of thing you’ll be computing at runtime on a 16-bit processor with no hardware floating point capability. There is at least an easy workaround in this case, as we can create lookup tables for the matrix constants.

Finally, well, I’d need to learn 65816 assembly. Maybe someday?